Day 3

The gender imbalance

Story by Teri Pecoskie

Teri Pecoskie is an award-winning multimedia journalist and The Spectator's education reporter. She also co-authored the landmark BORN: A Code Red Project series, which was awarded the country's highest investigative journalism honour in 2012.

Teri has covered issues related to school achievement since she started at The Spectator in 2010.

Photographs by John Rennison

Web design by Pete Smaluck

Published April 15, 2014.

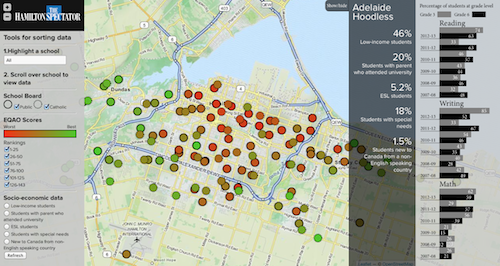

Interactive map: Find your school's scores

Paul Denomme has a problem. His boys are falling behind.

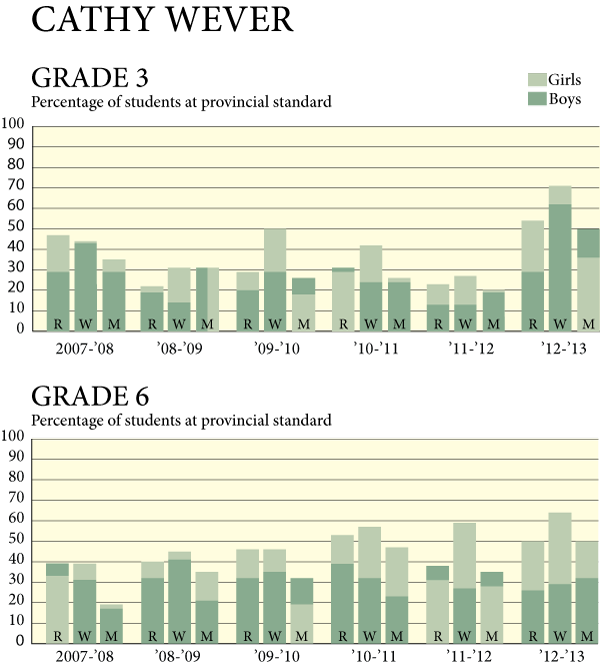

At Denomme’s school, Cathy Wever, boys aren’t having the same success as girls on provincial tests. They haven’t for years, especially when it comes to reading and writing.

“I think we want all of our students to be engaged and we want them to be learning at their best,” says the principal of the Wentworth Street school.

Denomme isn’t the only one asking that question. Across the city, province, and even the globe, boys have fallen behind girls in achievement, particularly when it comes to literacy – a skill necessary for learning in any subject.

It’s not a new trend.

According to a 2009 research paper from Ontario’s Education Quality and Accountability Office, girls’ superiority in reading and writing has been “a widely observed, relatively static pattern” for at least the last four decades.

There are rare instances of boys performing similarly to girls in literacy, the paper adds, but there are no reported studies in which boys performed better than girls in reading and writing.

The Spectator’s analysis of six years of standardized test scores at Hamilton’s Catholic and public elementary schools backs that up.

Take the nine schools – Catholic and public – for which all the gender-based data was available.

In those schools, the pass rate for girls was higher than that for boys on at least 70 per cent of EQAO tests over the past six years. In reading and writing, it was higher still – with girls coming out on top at least 82 per cent of the time.

The board-level results are even less promising. Since 2008, the pass rate for girls has been higher than that for boys in almost every subject on every Grade 3 and 6 EQAO test at both the Catholic and public school boards.

“I personally see it as a major, major issue,” says Hamilton-Wentworth Catholic District School Board chair, Pat Daly. “We have done all kinds of creative things, thanks to the good work of our administration and principals and teachers, and have made some headway. But, in saying that, the gap is still unacceptable.”

What’s interesting about this particular challenge is that, unlike differences in overall achievement, it crosses social and economic strata.

That is, the gap in the percentage of boys and girls meeting the provincial standard at the city’s most advantaged schools is comparable to the gap at less advantaged schools, although outcomes at those schools are, in general, worse.

Daly says his board identified the lag in boys’ achievement as a challenge close to 20 years ago. He and his fellow trustees have been calling on the province and education ministers ever since to recognize the issue and provide resources.

In short, he knows he needs help.

“I think it needs to be said that this is more than any one school or school board can do on their own.”

The percentage of students at the provincial standard, on average, from 2008-13.

R - reading, W - writing, M - math

Principal Paul Denomme wonders why the boys at Cathy Wever school are behind in literacy. It's a question that confounds educators around the world.

Alittle more than five years ago, the EQAO recruited some of Ontario’s top education experts to study the differences in literacy achievement between boys and girls.

Their findings were clear-cut.

Girls were shown to have a consistent and significant advantage over boys when it comes to reading and writing. And it’s happening across borders – in other countries, cultures and languages as well.

What the researchers couldn’t nail down, however, was an explanation for the differences. They also found the interventions or strategies that might successfully address them were largely unknown.

Since then, there’s little progress to report.

“There’s no doubt that it’s happening,” says Don Klinger, one of the study co-authors. “The question you’re asking is ‘why?’ And that’s the answer nobody has.”

Klinger is associate dean of graduate studies for the faculty of education at Queen’s University in Kingston. He also works closely with the EQAO as a researcher and consultant.

While Klinger can’t shed much light on what is driving the gap in achievement between boys and girls, he’s happy to offer some insight on what isn’t.

As far as he and his research partners can tell, the disparities aren’t rooted in student attitudes. “Boys dislike writing,” he explains. “End of story.” Regardless of whether they are high or low achievers.

People also talk about what Klinger terms “the feminization” of the curriculum, or the idea that classroom teaching and assessment is slanted towards girls.

There’s no evidence of that either, he says.

“We probably have more male teachers now in elementary school than we did a while ago, especially at the elementary level, but it hasn’t made a difference.”

Magdalena Janus, an expert in early childhood education, has an alternative explanation as to why boys don’t do as well as girls on EQAO tests.

It could be genetics.

As a gender, says the McMaster University professor, boys are generally more vulnerable. They have less genetic backup for certain faults and failures, which is why they tend to show up more often in a number of childhood disorders.

That could end up influencing the way we’ve learned to socialize boys and work with them, says Janus – at home, for instance, or in class. Maybe it spills over into their achievement.

While genetics are a factor, however, they’re not deterministic. That is, boys aren’t automatically in line for lower scores.

If they were, says Janus, you wouldn’t see any men succeeding, which is obviously not the case.

“You really have to experience a bunch of other factors in order for this to translate into some difficulty,” she says.

AUDIO: Public school board chair Jessica Brennan weighs in on the differences in achievement between boys and girls

Sarah Brown sees a difference between the genders in her class.

The boys gravitate to math and numbers, says the Grade 3 teacher, while the girls are more into reading and writing.

The girls, she adds, will sit still and get involved in their work, “and the boys generally like to be active – so not always engaged.”

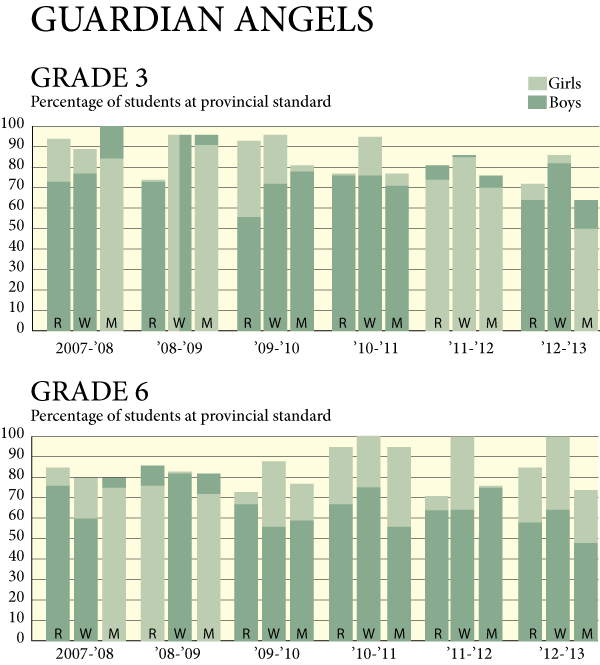

Brown’s been teaching awhile, but it’s her first year at Guardian Angels, a Waterdown school bursting at the seams.

Compared to other schools, the boys there have been successful when it comes to EQAO tests. But they still don’t pass as often as the girls.

Since 2008, the girls at Guardian Angels have outperformed the boys on two-thirds of the Grade 3 tests. In Grade 6, the differences were even more pronounced, with the girls having a higher pass rate 90 per cent of the time.

“I wouldn’t say it’s a problem in so many words, but it’s definitely something that needs to be addressed,” Brown says.

The question is, how?

For Brown, it means doing whatever she can to engage her students. This year, for instance, she stocked her classroom library with books about hockey in a deliberate attempt to get her boys to read more.

They’ve turned out to be a big hit.

“Every class is different, so you have to work with the dynamics of your class and the interests of your class,” Brown says. “That’s how I look at it.”

The percentage of students at the provincial standard, on average, from 2008-13.

R - reading, W - writing, M - math

Gender Differences

In schools all across Hamilton, girls tend to outperfrom boys on EQAO tests.

Scroll over the map to see some of these differences.

The numbers represent percentage of students at the provincial standard, on average, from 2008-2013.